While financial forecasting involves intense calculations and number crunching, it also involves dealing with complicated accounting terms.

Terms that sound almost the same but mean very different things—polar opposites at times.

Fixed and current assets are one of those examples. They confuse entrepreneurs all the time. The truth? They’re both important, but for totally different reasons.

In this article, let’s break down the differences so you can use them confidently in your forecasts.

What are fixed assets?

Fixed assets are the long-term resources you hold to keep the business running—property, machinery, and equipment. They’re not meant to be sold off for quick profit or used up in production within the fiscal year, which is why they sit under non-current assets on the balance sheet.

That’s the accounting version. Here’s how I think about it as a VC analyst: Fixed assets are the big, durable things that keep your business running year after year. They don’t move fast, and they don’t turn into cash easily, but they’re what allow you actually to do business.

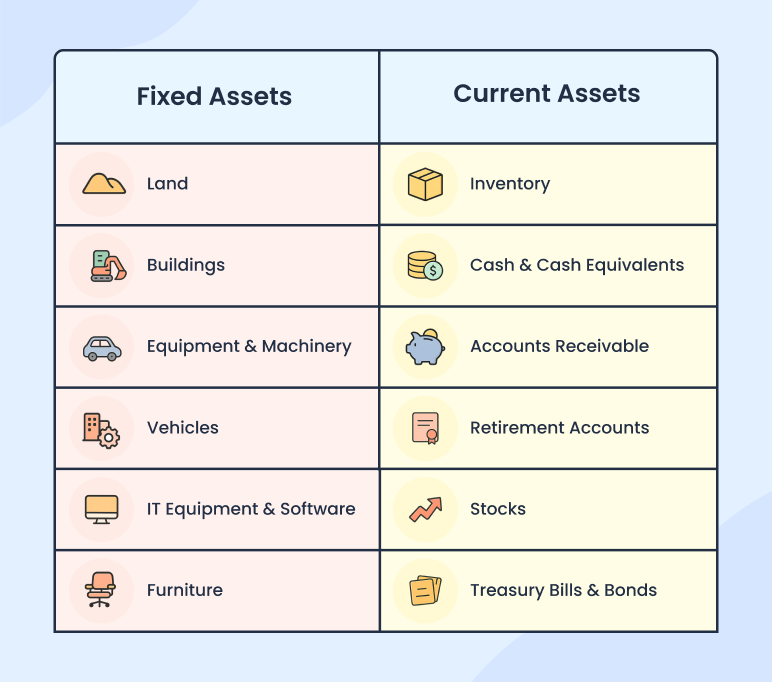

Examples of fixed assets

- Property (offices, warehouses, land)

- Equipment and machinery

- Vehicles used in operations

- Furniture and fixtures

- Technology infrastructure (servers, specialized hardware)

What are current assets?

Current assets are short-term resources a business owns that are expected to be converted into cash, sold, or used up within one year.

Basically, current assets are your company’s day-to-day fuel. They’re the resources that keep operations moving and bills paid in the short run. Cash in the bank, money customers owe you, or products sitting in the warehouse; these are the things you can turn into liquidity quickly.

Current assets example

- Cash and cash equivalents

- Accounts receivable (customer invoices due)

- Inventory ready for sale

- Prepaid expenses (rent, insurance, services)

- Marketable securities (stocks or bonds that can be sold quickly)

These are the assets that tell me how much flexibility your business has right now.

Fixed assets vs. current assets (comparison)

Often, I see founders thinking of “assets” as one big bragging right: The more you own, the stronger your business looks. But investors don’t read it that way. We separate fixed from current because they answer two very different questions:

- Can this company survive the next 12 months?

- Can this company build value over the next 5 years?

Here’s how I break it down when I review financials.

1) Purpose: Why split them at all?

Fixed assets show where you’ve committed resources for capacity and growth. Current assets show whether you can actually keep the business running today. Investors need both views: One shows scalability, the other shows survival.

You might ask, “But if I own expensive equipment, isn’t that a strength?”

It is, but only in the long game. In the short game, it won’t help you pay salaries next month. That’s why I separate the two, so I can see whether you’re both surviving and building.

| Investor question | Current assets | Answered by current assets |

|---|---|---|

| Can the business scale over 5 years? | Yes—factories, servers, equipment drive capacity | No—they’re used up or cycled within a year |

| Can the business survive the next 12 months? | No—can’t liquidate fast | Yes—cash, receivables, inventory, fund operations |

2) Lifespan: How long do they last?

Fixed assets lose value gradually through depreciation, which is meant to reflect their actual economic life. A truck or machine may run for 5–10 years, but replacement costs must be planned for in advance.

Current assets cycle much faster, but what is important is whether they turn when expected. Receivables sitting for 120 days or inventory piling up in storage weaken liquidity.

But what about prepaid expenses? Let’s say you pay your office rent or insurance premium upfront. On paper, it’s recorded as a current asset. Why? Because the benefit stretches over the coming months.

Though it’s not the cash you can spend again, it still improves your short-term position by covering costs you’d otherwise need cash for later in the year.

| Asset type | Typical useful life | Investor lens |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed assets (property, machinery, vehicles) | 5–10+ years | Predictable depreciation, but replacement costs must be forecast |

| Current assets (cash, receivables, inventory) | < 12 months | Liquidity check—do they actually turn fast enough? |

3) Liquidity: How quickly can they be turned into cash?

Fixed assets tie up capital. You could sell machinery or buildings if you had to, but not without taking a hit and disrupting operations. They’re valuable, but they don’t translate into ready cash.

Current assets, by contrast, are built for liquidity. Cash is already liquid, receivables should turn into cash in weeks, and inventory is meant to cycle into sales within months. That’s why they’re critical for day-to-day survival.

Not all current assets are equally reliable. Receivables only help if customers actually pay on time. Inventory only helps if it moves before it becomes obsolete. A warehouse full of unsold stock doesn’t strengthen your liquidity; it drains it.

That’s why I always look past the headline number to see whether those “current” assets are truly cash-ready.

4) Revaluation reserve: When asset values change?

Fixed assets sometimes rise in value. Land is the classic example; it doesn’t depreciate, and under certain accounting rules, it can even be revalued upward. When that happens, companies may create a revaluation reserve to reflect the increase on the balance sheet.

Current assets don’t work that way. You won’t see a “revaluation” for cash, receivables, or inventory. Their worth is already tied to market or face value, so there’s no reserve involved.

Intangibles, like software licenses or trademarks, are a gray area. They’re usually treated as fixed assets, but instead of being revalued, they’re amortized over time. The exact treatment depends on accounting standards (GAAP vs. IFRS).

Revaluation always looks nice on paper, but I don’t read too much into it. A building worth more today doesn’t mean your business is generating more cash. What matters is whether your assets are fueling operations.

5) Finance: How are they funded?

If you buy a factory, a fleet of trucks, or a software platform (fixed assets), you expect them to generate returns for years. The funding should match that horizon (equity or long-term debt) so you’re not scrambling to repay a loan before the asset has even paid for itself.

Current assets, such as cash, receivables, and inventory, all turn over within months, so they’re typically financed with short-term credit: supplier terms, overdrafts, or working capital loans.

A SaaS company, with minimal fixed assets, doesn’t need heavy long-term financing, but it does need to manage receivables and cash cycles carefully. A logistics or manufacturing company, by contrast, lives on fixed assets, so long-term financing is unavoidable.

As a general thumb rule, I check if the funding life matches the asset life. If short-term cash is being used to finance long-term bets, that’s a red flag. It tells me management may be papering over liquidity gaps instead of building stable growth.

6) Pledge: Can assets be used as collateral?

Fixed assets back up your borrowing. Companies pledge land, buildings, or machinery to secure long-term loans. Banks like it because those assets hold value even if the business stumbles.

Current assets don’t give you the same leverage. Sure, you can finance receivables through invoice discounting or borrow against inventory, but lenders usually treat that as riskier. Cash, of course, doesn’t get pledged; it’s already liquid.

Founders often ask me: “Why should I care about collateral if I’m raising equity, not bank debt?” The answer is: Banks and investors both watch your ability to raise capital.

If you’ve got fixed assets to pledge, banks will lend cheaper and longer, which means your future financing options are stronger. If you don’t, you’re reliant on cash flow alone, and that’s a much tighter rope to walk.

I wouldn’t invest in companies because they own buildings or trucks. But I do notice that when collateral is available, it gives the business flexibility.

7) Sale of an asset: How is it treated?

When you sell machinery, land, or vehicles, the result is a capital gain or loss. It’s not part of day-to-day operations, so it gets reported separately, often under extraordinary items on the P&L.

Selling current assets is the opposite. That’s your core business. The sale shows up as revenue, and the margin on it flows through to profit or loss in the normal course of operations.

You might ask, “But if we sold an old warehouse at a gain, isn’t that proof we’re profitable?” Not really.

It shows you realized value on an asset, but it doesn’t say anything about whether your business model is generating sustainable profits. When I see earnings boosted by one-off sales of fixed assets, it raises a flag. Are we looking at healthy operations, or a company covering gaps by liquidating the furniture?

| Sale Type | Accounting Treatment | Investor Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed asset sale (e.g., warehouse) | Reported as capital gain/loss, outside core ops | One-off boost — not proof of business health |

| Current asset sale (e.g., inventory) | Recognized as revenue, part of P&L | Core operations—shows whether the business model works |

Fixed vs. current assets in your financial statements

I’ve seen companies with millions in assets fail to pay salaries on time. Why? Liquidity and lack of current assets. While they were set for the long term with millions invested in machinery and equipment, they’d very little in current assets.

That’s why I always separate fixed from current before trusting a single ratio. Here’s how that split really plays out in the three statements investors rely on:

1) As a part of your balance sheet

On a balance sheet, current assets are listed first by liquidity, while fixed assets sit under non-current. The order highlights what matters most: Short-term survival before long-term bets. That’s why lenders lean heavily on the current ratio.

From my perspective, a balance sheet that “balances” doesn’t tell me much. What is important is the mix. I’d put more weight on $500k of receivables that convert in 30 days than on $5M of machinery that can’t be liquidated without disrupting operations.

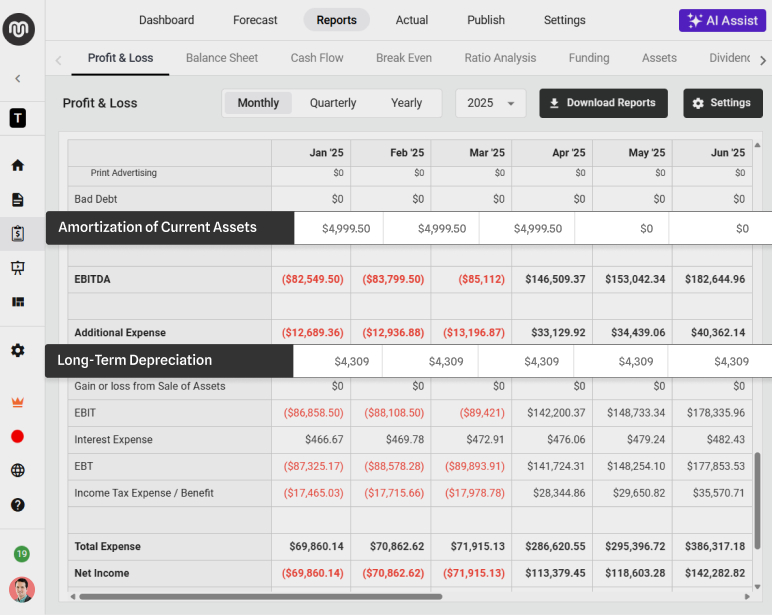

2) As a part of your Profit & Loss (P&L) statement

Fixed assets show up as depreciation or amortization, not direct line items. Current assets flow more visibly: Inventory hits cost of goods sold, receivables convert to revenue.

Forecasts must connect both sides. CapEx creates future depreciation, and sales growth demands more inventory and receivables. When I review a P&L, I ask:

- Are revenues backed by collections, not just invoices?

- Do margins hold once inventory costs are factored in? Is depreciation tied to productive assets?

A P&L that flatters without cash or alignment shows weak fundamentals.

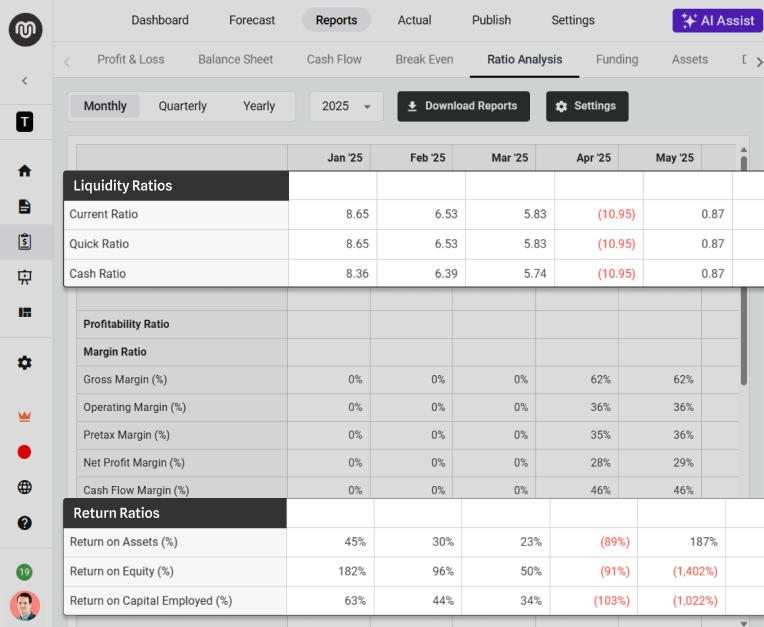

3) In financial ratios and investor analysis

Financial ratios depend on what sits behind them. A current ratio looks strong until receivables drag 120 days or inventory moves once a year. Return on assets also shifts by industry—a SaaS firm looks lean, a logistics company looks asset-heavy.

Even fixed asset turnover has baselines: Industrials average ~8.5, Technology ~13.0, Communication Services above 30. (source) If you don’t know what’s fixed vs. current in your own numbers, you can’t explain why these ratios look the way they do, and neither can I as an investor

4) In business planning and forecasting

Forecasts fall apart when asset needs don’t match the growth story. If sales double but receivables and inventory stay flat, the model is unrealistic. So what looks like growth on paper will quietly drain cash in reality.

In planning, I check alignment: Fixed asset investments should be built into CapEx plans, while current assets must scale with revenue.

Funding also matters—long-term bets should be financed with long-term capital, working capital with short-term credit. When those pieces line up, forecasts feel credible. When they don’t, it’s usually a sign that liquidity risks are not being addressed.

The bottom line

At the end of the day, fixed assets vs current assets isn’t just an accounting split; it’s the clearest test of whether a founder understands both survival and scale. The founders I take seriously are the ones who can point to their own statements and explain how each piece plays into liquidity, ratios, and forecasts.

And if building that clarity feels like a grind, that’s exactly where Upmetrics helps. It takes those same financial statements, highlights the splits, and shows you (and your investors) whether your assets are fueling short-term survival and long-term growth.